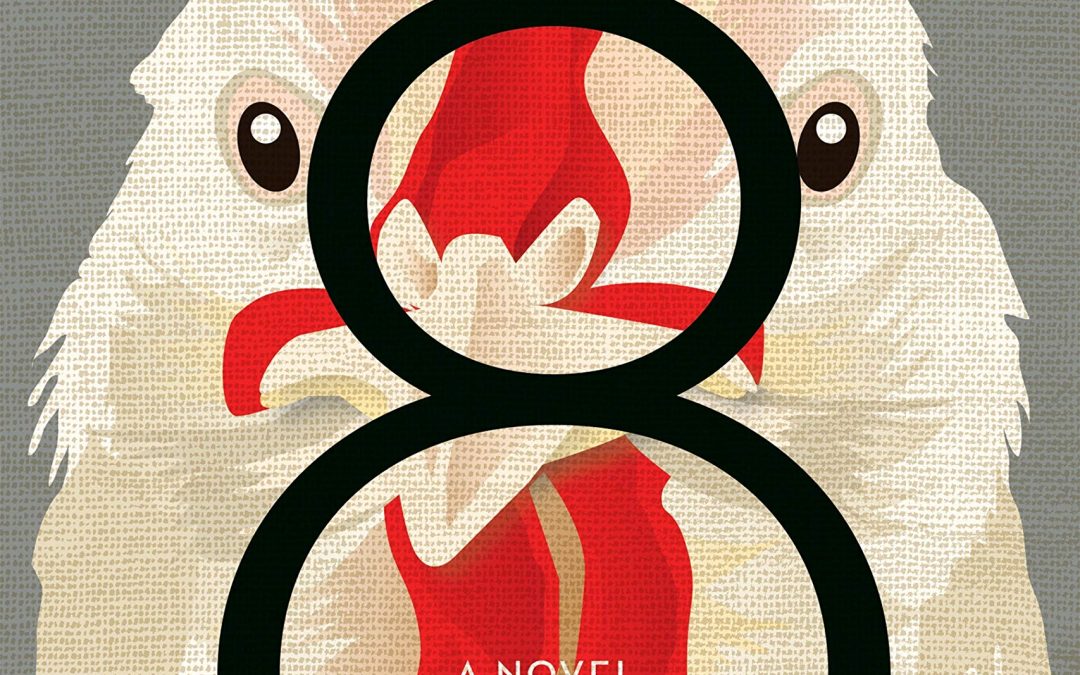

By Deb Olin Unferth

While the characters of Barn 8 are exceedingly compelling, the novel is fundamentally an ode to the humble chicken and a critique of factory farming wrapped up in a darkly comical heist plot. The subject of animal rights is addressed with urgency and passion, but the book succeeds because of Deb Olin Unferth’s light touch. Rather than harangue, she gently pleads for empathy on behalf of creatures who cannot speak for themselves.

The novel begins with 15-year-old Janey Flores arriving in Iowa to meet her father for the first time, having just learned his name and location from her mother. The two clash from the outset, and Janey is about to return home to Brooklyn when she gets a call telling her that her mother has been killed in a car accident. The novel flashes forward five years and Janey’s dad arranges a job interview for her at the USDA, where he works. She’s interviewed and hired as a “layer hen consumer auditor” by Cleveland Smith, a woman who, coincidentally, Janey’s mother used to babysit. The two visit local chicken farms to verify they are following USDA regulations, but each gradually becomes radicalized from seeing the miserable conditions in which the animals live. They begin liberating chickens together and dropping them off at a local animal shelter. In the process, they meet Dill, an animal rights activist and recovering drug addict. They eventually convince him to go along with their plan to free the entire population of Happy Green Family Farm—a million hens—for which he recruits his old friend Annabelle, along with every other animal activist they know. The third person omniscient narrator alternates among the perspectives of these characters, along with a few other key figures (and hens).

Dramatic tension escalates as the plan is organized and put into motion, and each character’s personal motivation is explored with tender care. Janey and Cleveland, who are both restless and lost, quickly form a symbiotic bond with one another, in part because of their mutual affection for Janey’s mother. Freeing the hens provides them both with a sense of purpose and accomplishment, and Janey feels happy and alive for the first time since her mother’s death. Dill, meanwhile, is losing his tenuous grip on sobriety as his husband prepares to leave him. Annabelle is the black sheep of the Green family (of Happy Green Family Farm) who went off the grid to live alone on a chemical waste contamination site. Annabelle’s ex-husband, former activist Jonathan Jarman Jr., has made a more conventional life for himself in recent years with a steady girlfriend and her kids, but he cannot resist the siren song of his ex-wife and the excitement and chaos that invariably follow her.

While there are blunt descriptions of the conditions in which hens live on a factory farm that will be disturbing to some readers, the more difficult passages are tempered by Unferth’s dry wit and the overall farcical depiction of the heist. The hundreds of veteran animal rights activists who gather to go over the liberation plan are described drolly contemplating the impossibility of ideological purity: “They had been there for the fast-food battles, had cheered when McDonald’s agreed to go cage free. Now they found themselves in the preposterous position of having to approve of eating eggs at McDonald’s.” Furthermore, the novel is not a morality play. The activists are hapless misfits trying (for the most part) to do the right thing, but Annabelle’s brother, the manager of Happy Green, is rendered with just as much sympathy. That is to say, readers who eat meat will walk away feeling perhaps uncomfortably enlightened about conditions on an egg farm, but not judged or scolded.

Though the plot is a chaotic tumult punctuated with comic hijinks, Barn 8 also has an emotionally astute message about personal agency, freedom and fulfillment. Chickens, the author assures us, will be okay (as a species, not necessarily these specific chickens). The animal she refers to as “T. Rex’s pretty little niece” will not be trapped in our cages enduring barbaric conditions forever. But what about us? Unferth suggests that if we care about something enough to risk going to prison for it, if we love someone enough to sacrifice stability and comfort to follow them to the ends of the earth or to stand by them at their worst, maybe our species will endure like the modest but mighty chicken.

Reviewed by Lisa Butts