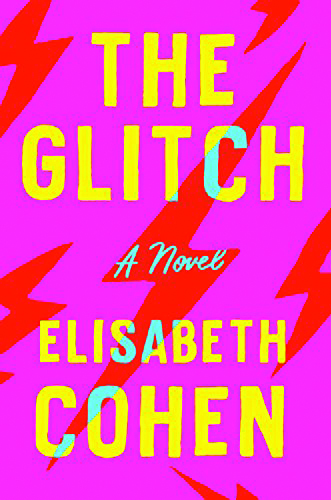

By Elisabeth Cohen / Doubleday, May 2018

Every once in a while, I find myself wondering how the minds of truly successful people work. Not the glimpses we might see in interviews, or the “helpful tips” they give out in magazine articles or books, but truly what their everyday thought processes are like. Are they really that different from us? Elisabeth Cohen’s new novel, The Glitch, gives us a terrifying example in Michelle “Shelley” Stone, a CEO whose wearable technology company, Conch, is the center of her universe. Shelley is a woman who eats, sleeps, and breathes business in a way that seems not just abnormal, but almost inhuman. Her life doesn’t just revolve around work; it defines her. She wakes up in the middle of the night while on vacation to take conference calls; she carries around extra product in her purse to give away as promotional gifts; she even takes power naps standing up while waiting in line so she can be more “efficient.” But what’s most strange is her attitude about it: she enjoys this kind of life, to the point where she finds herself more comfortable at work than at home with her husband and children. I found myself thinking, “If this is what it takes to be successful, how does anyone manage it…and who would want to?”

But something shows up to throw a bit of a monkey wrench in Shelley’s well-oiled machine of a life; namely, Shelley herself. While on vacation, she runs into someone who bears more than a passing resemblance to her younger self, right down to a distinctive scar on her shoulder. While Shelley vacillates between wondering whether her past has literally come back to haunt her, or if she is simply losing her mind, the rest of her world decides to upend as well – with wide-ranging consequences.

I have to admit: this book left me pretty stressed out. The idea that anyone would have to be this way to be considered successful made me completely rethink my feelings on the matter. But it also made me seriously wonder about how much of this description is more accurate than we as a society would like to admit. How many companies these days publicly touting their “work-life balance” policies privately penalize their employees for their work not becoming their lives? Is this level of career obsession becoming the new norm? If so, maybe this book is less a fictional tale than a cautionary one.